- By Vasudev Ram - Online Python training / SQL training / Linux training

Pipeline image attribution

Hi readers,

Long time no post. Sorry.

I saw this programming problem about removing lines from a file on Rosetta Code.

Rosetta Code (Wikipedia) is a programming chrestomathy site.

It's a simple problem, so I thought it would make a good example for Python beginners.

So I wrote a program to solve it. To get the benefits of reuse and composition (at the command line), I wrote it as a Unix-style filter.

Here it is, in file rmline.py:

# Author: Vasudev Ram

# Copyright Vasudev Ram

# Product store:

# https://gumroad.com/vasudevram

# Training (course outlines and testimonials):

# https://jugad2.blogspot.com/p/training.html

# Blog:

# https://jugad2.blogspot.com

# Web site:

# https://vasudevram.github.io

# Twitter:

# https://twitter.com/vasudevram

# Problem source:

# https://rosettacode.org/wiki/Remove_lines_from_a_file

from __future__ import print_function

import sys

from error_exit import error_exit

# globals

sa, lsa = sys.argv, len(sys.argv)

def usage():

print("Usage: {} start_line num_lines file".format(sa[0]))

print("Usage: other_command | {} start_line num_lines".format(

sa[0]))

def main():

# Check number of args.

if lsa < 3:

usage()

sys.exit(0)

# Convert number args to ints.

try:

start_line = int(sa[1])

num_lines = int(sa[2])

except ValueError as ve:

error_exit("{}: ValueError: {}".format(sa[0], str(ve)))

# Validate int ranges.

if start_line < 1:

error_exit("{}: start_line ({}) must be > 0".format(sa[0],

start_line))

if num_lines < 1:

error_exit("{}: num_lines ({}) must be > 0".format(sa[0],

num_lines))

# Decide source of input (stdin or file).

if lsa == 3:

in_fil = sys.stdin

else:

try:

in_fil = open(sa[3], "r")

except IOError as ioe:

error_exit("{}: IOError: {}".format(sa[0], str(ioe)))

end_line = start_line + num_lines - 1

# Read input, skip unwanted lines, write others to output.

for line_num, line in enumerate(in_fil, 1):

if line_num < start_line:

sys.stdout.write(line)

elif line_num > end_line:

sys.stdout.write(line)

in_fil.close()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Here are a few test text files I tried it on:

$ dir f?.txt/b f0.txt f5.txt f20.txtf0.txt has 0 bytes.

Contents of f5.txt:

$ type f5.txt line 1 line 2 line 3 line 4 line 5f20.txt is similar to f5.txt, but with 20 lines.

Here are a few runs of the program, with output:

$ python rmline.py Usage: rmline.py start_line num_lines file Usage: other_command | rmline.py start_line num_lines $ dir | python rmline.py Usage: rmline.py start_line num_lines file Usage: other_command | rmline.py start_line num_linesBoth the above runs show that when called with an invalid set of

arguments (none, in this case), it prints a usage message and exits.

$ python rmline.py f0.txt Usage: rmline.py start_line num_lines file Usage: other_command | rmline.py start_line num_linesSame result, except I gave an invalid first (and only) argument, a file name. See the usage() function in the code to know the right order and types of arguments.

$ python rmline.py -3 4 f0.txt rmline.py: start_line (-3) must be > 0 $ python rmline.py 2 0 f0.txt rmline.py: num_lines (0) must be > 0The above two runs shows that it checks for invalid values for the

first two expected integer argyuments, start_line and num_line.

$ python rmline.py 1 2 f0.txtFor an empty input file, as expected, it both removes and prints nothing.

$ python rmline.py 1 2 f5.txt line 3 line 4 line 5The above run shows it removing lines 1 through 2 (start_line = 1, num_lines = 2) of the input from the output.

$ python rmline.py 7 4 f5.txt line 1 line 2 line 3 line 4 line 5The above run shows that if you give a starting line number larger than the last input line number, it removes no lines of the input.

$ python rmline.py 1 10 f20.txt line 11 line 12 line 13 line 14 line 15 line 16 line 17 line 18 line 19 line 20The above run shows it removing the first 10 lines of the input.

$ python rmline.py 6 10 f20.txt line 1 line 2 line 3 line 4 line 5 line 16 line 17 line 18 line 19 line 20The above run shows it removing the middle 10 lines of the input.

$ python rmline.py 11 10 f20.txt line 1 line 2 line 3 line 4 line 5 line 6 line 7 line 8 line 9 line 10The above run shows it removing the last 10 lines of the input.

Read more:

Pipeline (computing)

Redirection (computing)

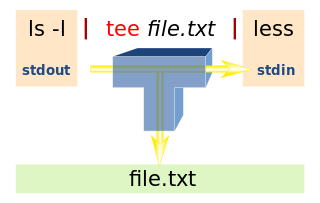

The image at the top of the post is of a Unix-style pipeline, with standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout) and standard error (stderr) streams of programs, all independently redirectable, and with the standard output of a preceding command piped to the standard input of the succeeding command in the pipeline. Pipelines and I/O redirection are one of the powerful features of the Unix operating system and shell.

Read a brief introduction to those concepts in an article I wrote for IBM developerWorks:

Developing a Linux command-line utility

The above link is to a post about that utility on my blog. For the

actual code for the utility (in C), and for the PDF of the article,

follow the relevant links in the post.

I had originally written the utility for production use for one of the

largest motorcycle manufacturers in the world.

Enjoy.